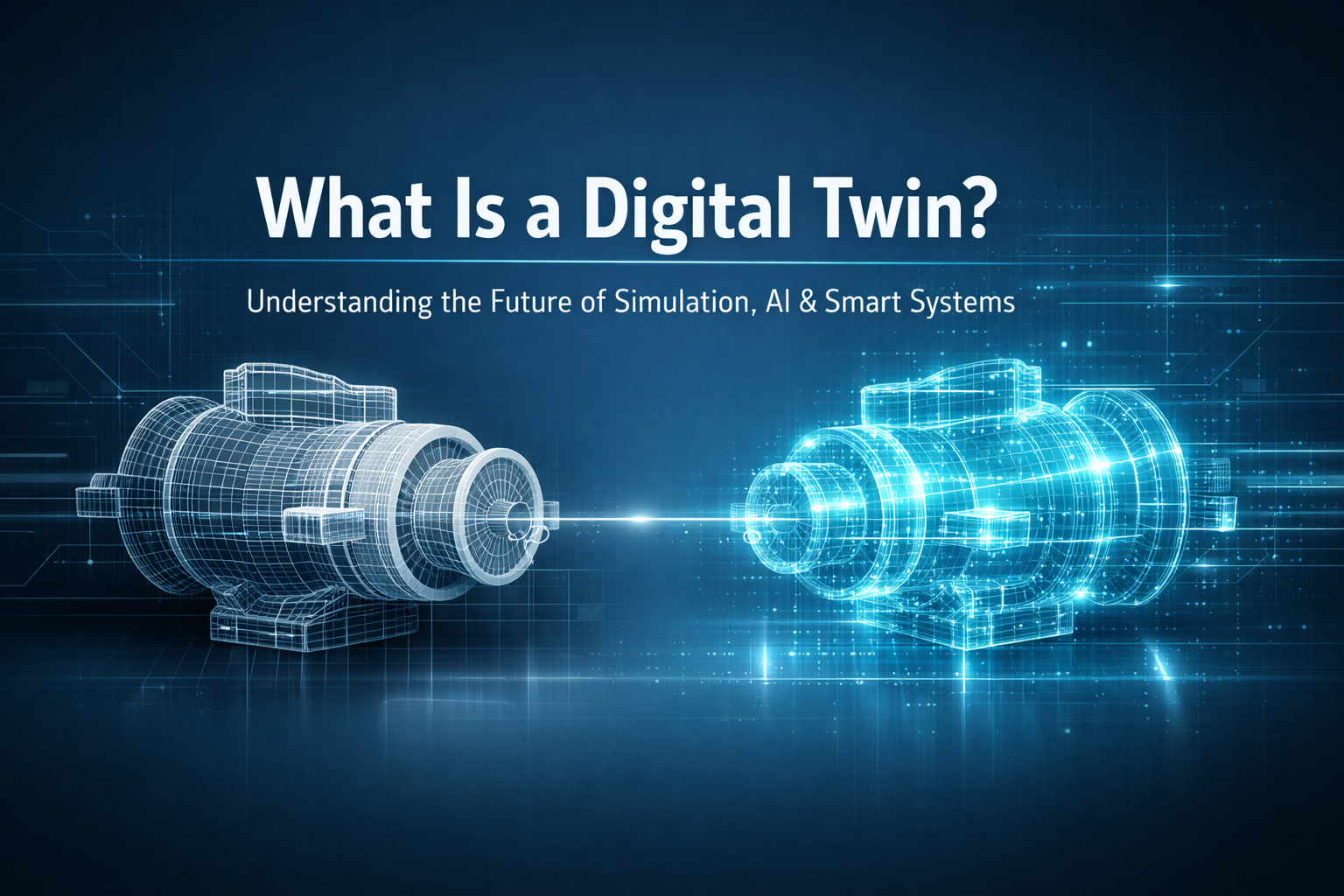

What Is a Digital Twin? A Developer’s Guide to Virtual Replication

The concept of a digital twin is rapidly moving from futuristic speculation to an essential component of modern engineering, IoT deployments, and complex system management. For developers building the next generation of intelligent applications, understanding what a digital twin is, how it functions, and why it matters is crucial. At its core, a digital twin is a dynamic, virtual representation of a physical asset, process, or system. It’s more than just a static 3D model; it’s a living counterpart updated in real-time by data streams from its physical twin.

Defining the Digital Twin Concept

A digital twin bridges the gap between the physical world and the digital realm. Imagine a complex machine on a factory floor—a jet engine, a wind turbine, or even an entire city infrastructure. The physical asset generates vast amounts of data via sensors: temperature, vibration, pressure, performance metrics, and location. This live data feeds directly into the digital model. This model isn’t just a simulation; it mirrors the current state, operational history, and contextual environment of its physical counterpart. Developers interact with this digital twin to perform analyses, test changes, and predict future behavior without ever touching the actual hardware.

This relationship is bidirectional. While data flows from the physical asset to the twin, insights, optimized configurations, or control commands generated within the digital twin can be pushed back to command the physical asset, creating a closed-loop feedback system essential for autonomous operations.

The Three Pillars of a Functional Digital Twin

To move beyond a simple dashboard or historical database, a true digital twin relies on three interconnected components. Developers need to architect systems that effectively manage these pillars to deliver real utility.

1. The Physical Asset and Sensor Layer (Data Ingestion)

This is the foundation. It encompasses the physical object equipped with sensors, actuators, and connectivity modules (often leveraging edge computing infrastructure). The primary technical challenge here for developers is ensuring robust, low-latency data ingestion. Protocols must be standardized, data cleanliness assured, and the volume of streaming data managed efficiently before it reaches the core twin application. This layer handles the translation of raw telemetry into meaningful digital input.

2. The Virtual Model (The Core Twin)

This is the actual digital representation. It typically involves sophisticated modeling techniques, often incorporating physics-based simulations, CAD models, and machine learning algorithms trained on historical operational data. This model must be dynamic. If the physical pump develops increased friction in Bearing A, the virtual model must reflect that change in its performance characteristics immediately. Developers spend significant time ensuring the fidelity and accuracy of this core model to guarantee that digital predictions translate accurately to physical reality.

3. The Connectivity and Analytics Layer (Insight Generation)

This layer ties everything together. It manages the continuous communication pipeline, stores the necessary contextual data (maintenance logs, environmental conditions), and hosts the analytical engines. These engines run predictive maintenance algorithms, simulate “what-if” scenarios, and optimize operational parameters. The output of this layer—the actionable insight—is what provides the return on investment for implementing a digital twin.

Practical Developer Applications and Use Cases

For software engineers, the digital twin environment offers rich ground for innovation beyond simple monitoring. It enables proactive, rather than reactive, system management.

Predictive Maintenance and Failure Analysis

Instead of scheduling maintenance based on arbitrary time intervals, the digital twin monitors component wear in real-time. By running simulations against the live twin, developers can precisely predict the remaining useful life of a part under current load conditions. This shifts maintenance from preventative to predictive, minimizing unexpected downtime.

Process Optimization and “What-If” Scenarios

Before deploying a significant firmware update or changing the operational parameters of a production line, engineers can test these changes exhaustively on the digital twin. If a new temperature profile yields better throughput in the twin, the corresponding commands can be deployed safely to the physical system. This sandbox environment drastically reduces risk in high-stakes industrial environments.

Design Iteration and Prototyping

In the design phase, a digital twin can be created even before the physical product exists, based solely on CAD models and expected performance parameters. Developers can iterate on the software controls and system logic concurrently with hardware design, speeding up the entire development lifecycle.

Key Takeaways

- A digital twin is a live, virtual replica of a physical asset or system, continuously updated with real-time sensor data.

- It requires robust data ingestion, a high-fidelity dynamic model, and powerful analytics capabilities to function effectively.

- For developers, digital twins enable complex scenario testing, advanced predictive maintenance, and risk-free process optimization.

- The technology fundamentally shifts system management from reactive monitoring to proactive, data-driven control.